Read Part 1 to see how FUs are calculated for pitchers during their appearances.

As we have learned in many different ways that are not a lot of fun, both relief pitchers and starting pitchers can succumb to the effects of pitching. This makes the Pitcher Abuse Point scale not appropriate for relief pitchers (see this article on Baseball Prospectus – (Jazayerli, 1998)). Other research has pointed to measures like innings pitched as being a poor determinant of workload in pitchers (Karakolis paper). Pitching on consecutive days, high velocities, and total pitches have been identified as risk factors for injury – let’s try and combine them all into one metric.

Starting with the FUs I described in part 1, I took a shot at modelling fatigue in every game in the 2015 MLB season. I downloaded the PitchFX database, and extracted the number of pitches, batters faced, innings pitched, and total time for each inning, for every game. I broke this down by pitcher, game, and inning, and was left with an FU for each inning during each game. To get a cumulative FU for each game, I just added these inning FUs up for each pitcher.

Velocity has also been indicated as a risk factor for injury, and the source of greater UCL stress (Whiteside et al., (2016), Sonne (2016)). To add in the effect of high velocity, a scaling factor was created using the average velocity of 92.16 mph. The peak velocity during each appearance was scaled to this, creating a factor that ranged between 0.614, and 1.124. This value was multiplied by the FU in each inning to create a velocity scaled FU.

Whiteside et al., (2016) showed reduced time between appearances was a significant predictor of UCL injury. Furthermore, the paper on heart rate variability in pitchers illustrated there weas less HRV the day after an appearance – which returned to baseline after 4 days. To include this in the cumulative FU, if a pitcher appeared in 2 games, back to back, they had a multiplier of 5. If their last appearance was between 2 and 4 days ago, they had a multiplier of 3. If their last appearance was 5 days or greater, the multiplier was 1. The velocity scaled FU was then multiplied by the rest multiplier, giving a cumulative FU for each game. These game cumulative FUs were then all added together, giving a season FU for each pitcher.

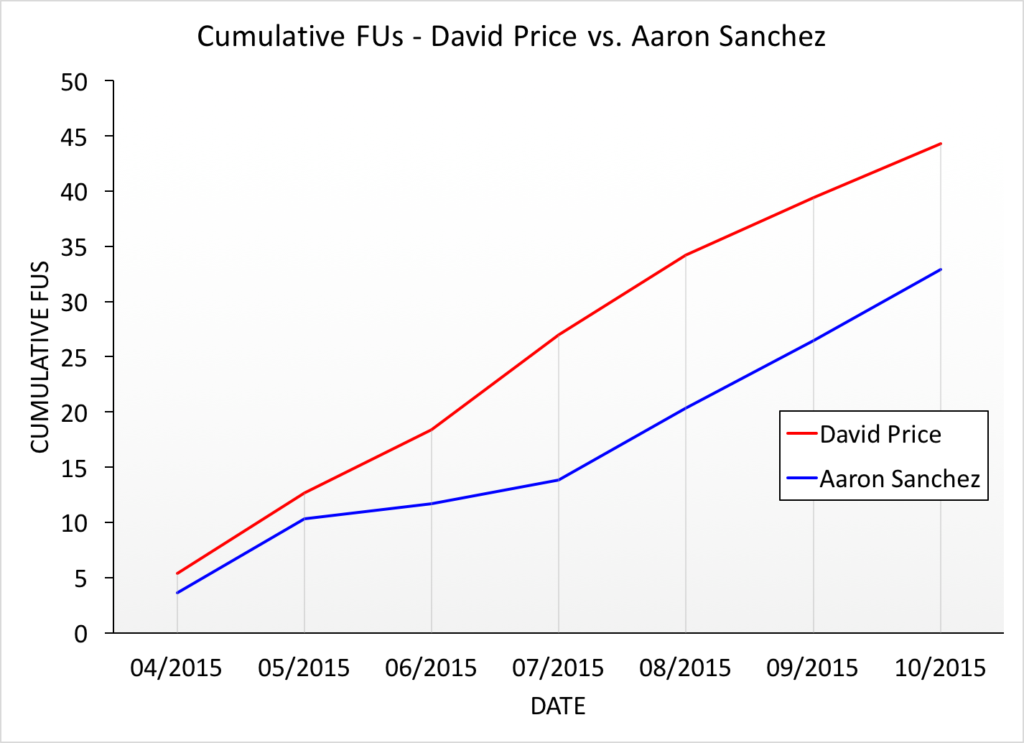

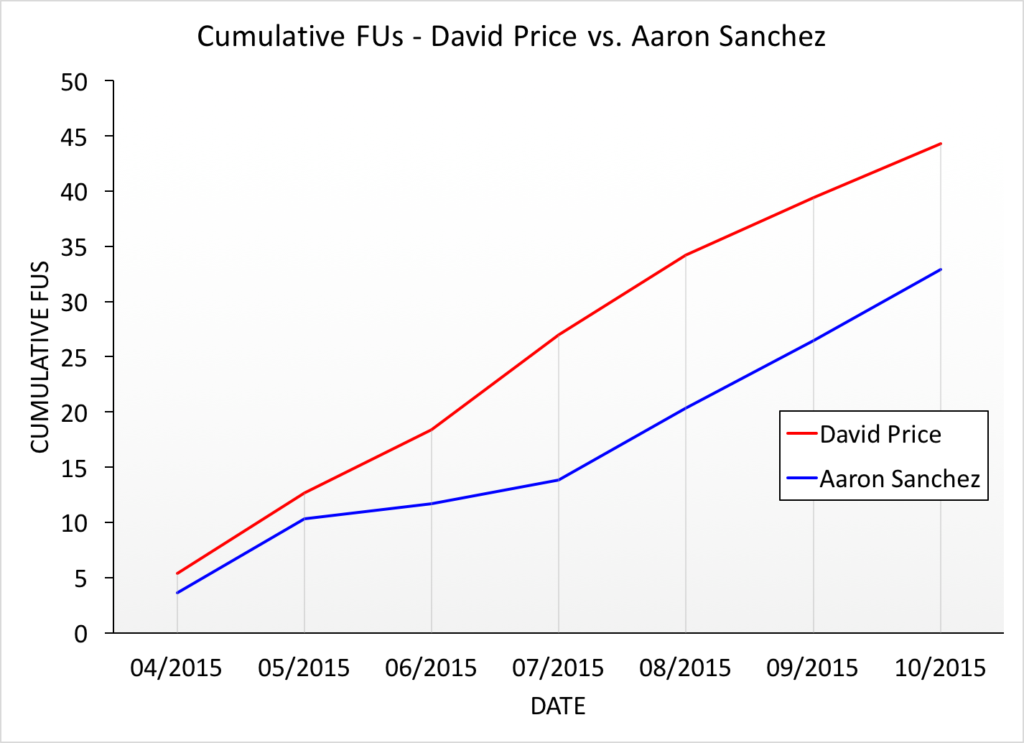

I’ve included an example of one pitcher from the 2015 season that I feel shows a good example of how this metric can be used (and how I feel moving a pitcher from the starting rotation to the bullpen doesn’t necessarily help their arm). Aaron Sanchez started the 2015 season as a starter for the Blue Jays, but injuries forced him to the disabled list after his June 6th start. When he returned on July 25th, Sanchez pitched out of the bullpen. To relate this back to the Whiteside article, which indicated higher velocities and fewer days’ rest were significant predictors of injury, Aaron averaged a peak fastball velocity of 95.5 mph as a starter in 2015, and 97.3 mph as a reliever. The average time between appearances was 5.5 days as a starter, but 2.4 days as a reliever.

I’ve compared his numbers against those of David Price – a known workhorse who remained in the starting rotation for multiple teams all year long.

Figure 1. Aaron Sanchez and David Price’s cumulative FU workloads during the 2015 season.

Despite Sanchez being moved to the bullpen, you can see that his cumulative FU’s still increase over the course of the season. Sanchez missed nearly two months in the 2015 season – and this can be seen in the plateau between May and July. When he returns from the bullpen, his workload begins to increase again, and matches the increasing trajectory of FUs generated by Price.

Given the research reported by Whiteside et al., (2016), and inferred from the Motus data collected at Driveline – I do not believe that Bullpen work should be viewed as a “break” from the starting rotation. There are unique demands associated with this type of pitching, and the workloads that the pitchers are subjected to when pitching in relief are not accurately captured by traditional metrics such as pitches thrown, or innings pitched. Let’s take a look at how Cumulative FU’s can capture the workloads of all major league pitchers from the 2015 season, and compare them back to the traditional metrics.

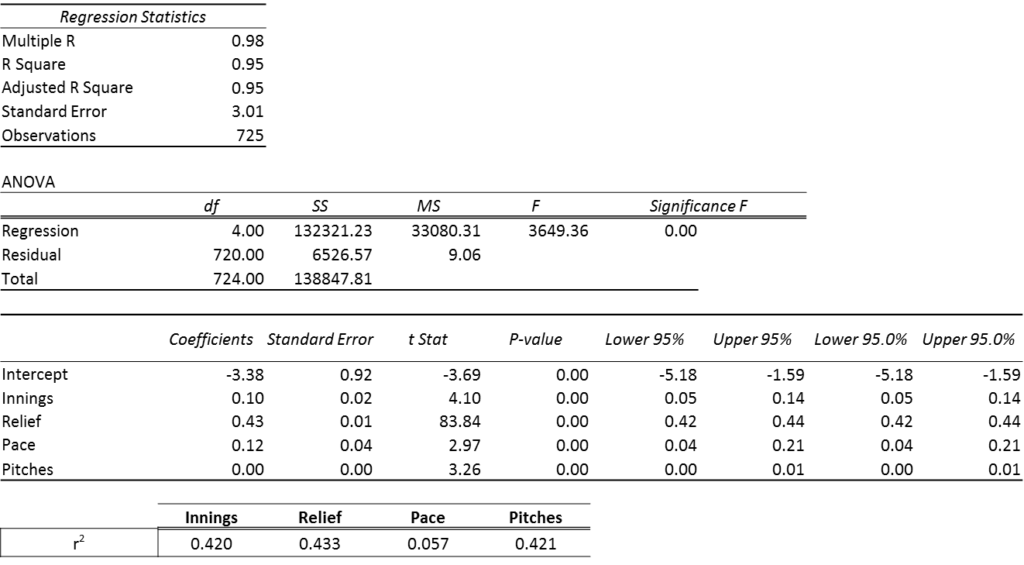

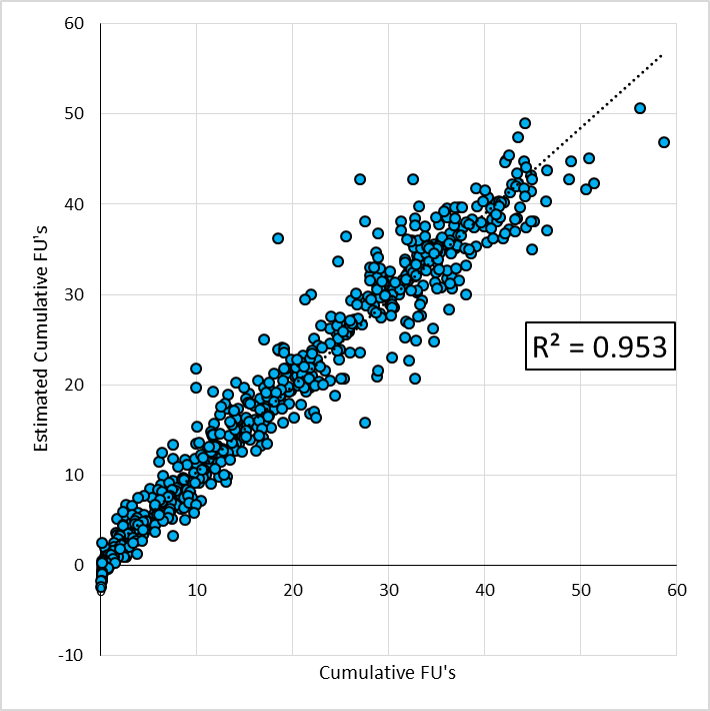

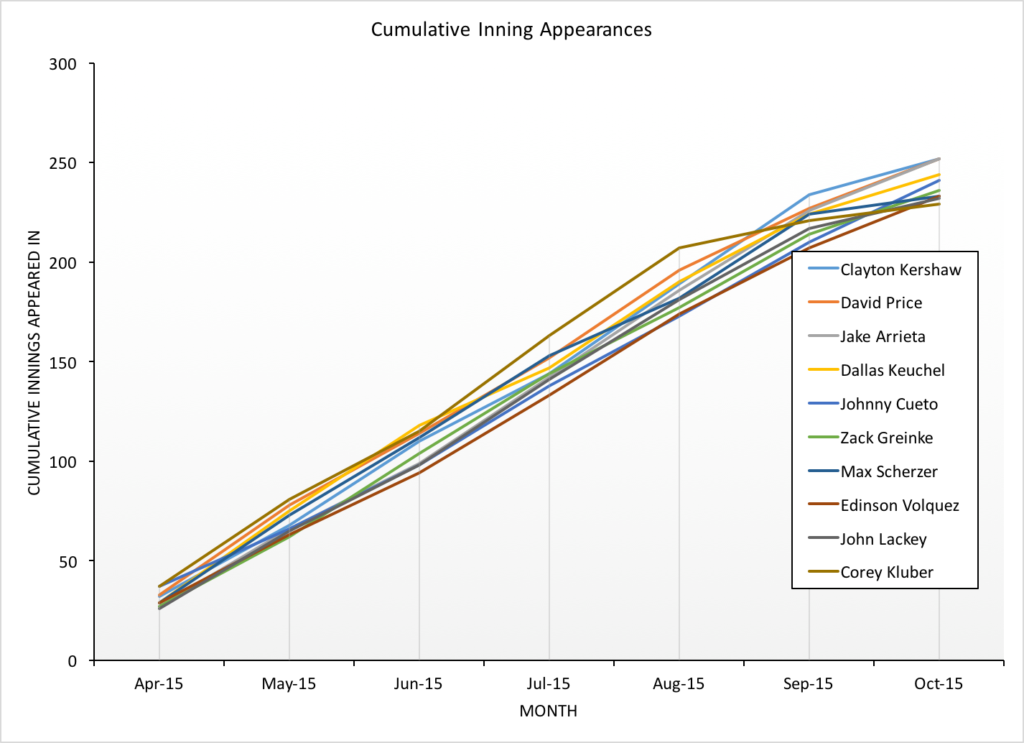

First, I wanted to see if the Cumulative FU was just a surrogate for IPs or pitches thrown – if it was, there is no point in using this metric! To do this, a Pearson correlation was used, and the R2 was calculated. Just as a note – this is not “innings pitched”, it represents “innings appeared in”. My thought process was – if a pitcher is coming out for an appearance, they perform the same warm up pitches, and bullpen work, regardless of how many outs they record. If a pitcher throws 30 pitches, while getting shellacked and does not record an out – this should still count towards the cumulative innings total on the season.

Cumulative FU’s were significantly correlated with other workload metrics, but not enough to believe they’re just a replication. After all, if you throw a lot of innings, that does represent a higher workload… it just may not capture the whole story. Looking at IP and total pitches, these measures explained 36.5% and 29.5% of the variance in cumulative FU’s, respectively. The number of outings in a season explained 65.2 % of the variance in cumulative FU’s, and the average number of days between appearances explained 27.9% of the variance in cumulative FU’s.

I examined the top workload pitchers for each of these metrics as well. I broke these metrics down by month of the season, so the cumulative workloads could be analyzed over time.

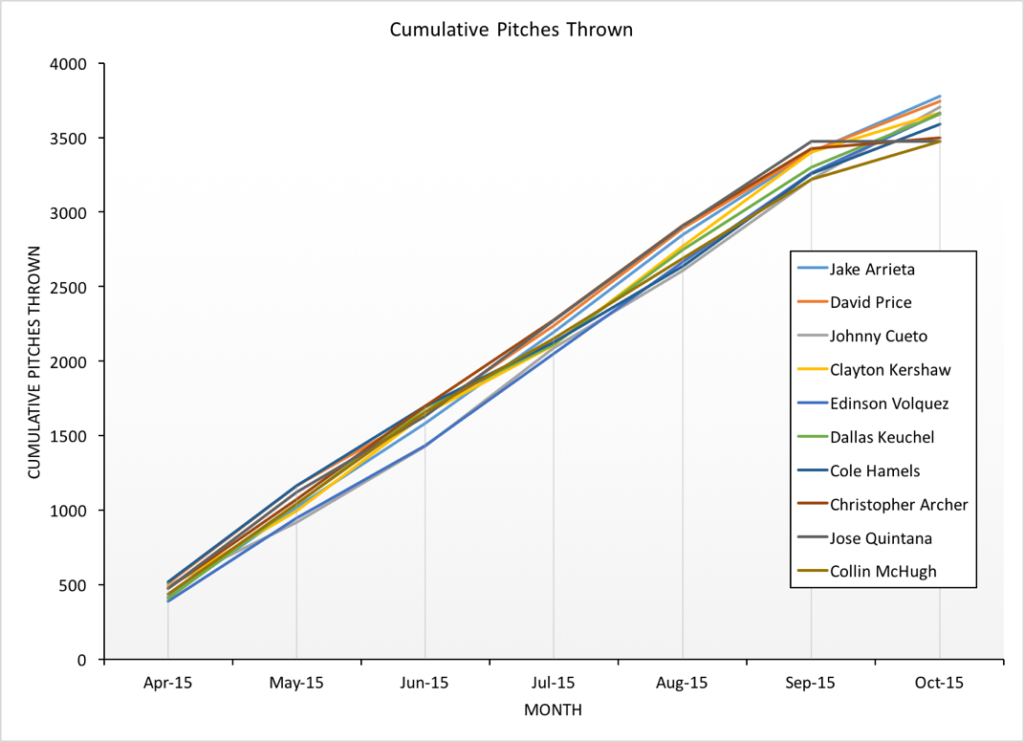

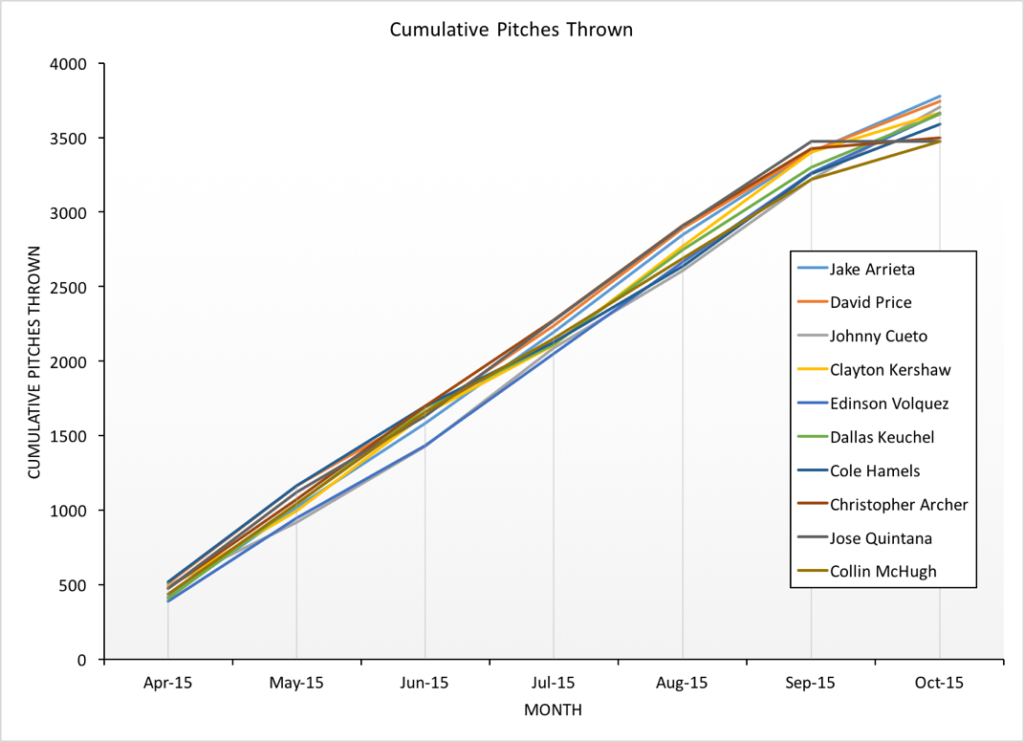

Figure 2. Cumulative Pitches Thrown during the 2015 season – top 10 pitchers.

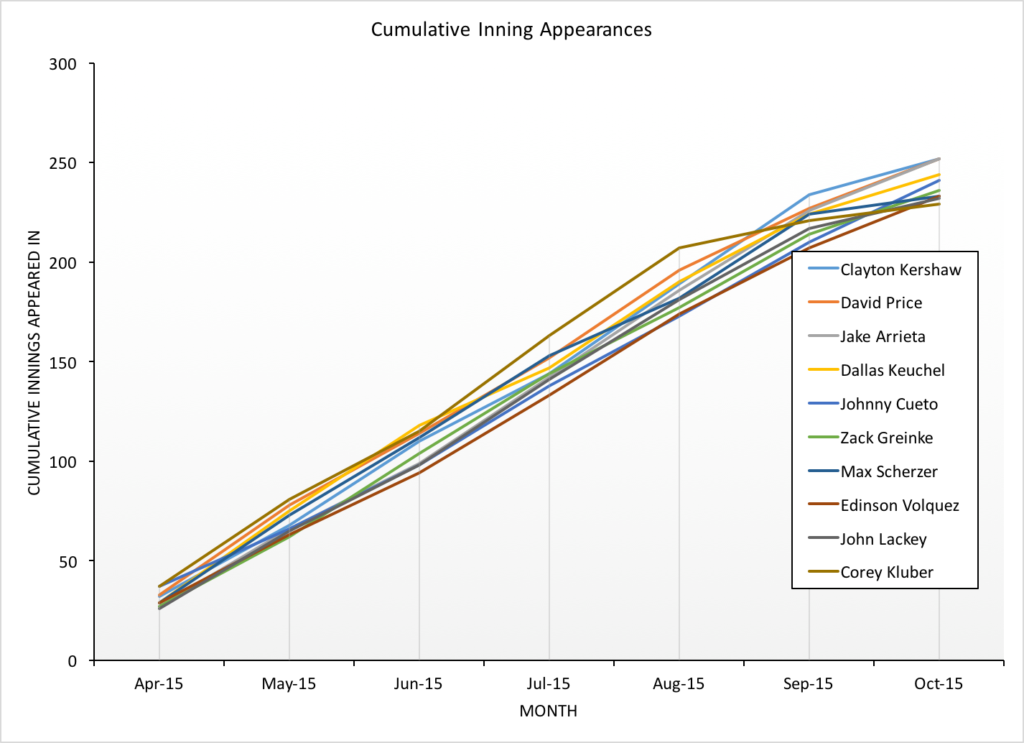

Figure 3. Cumulative Inning Appearances in the 2015 season, broken down by month.

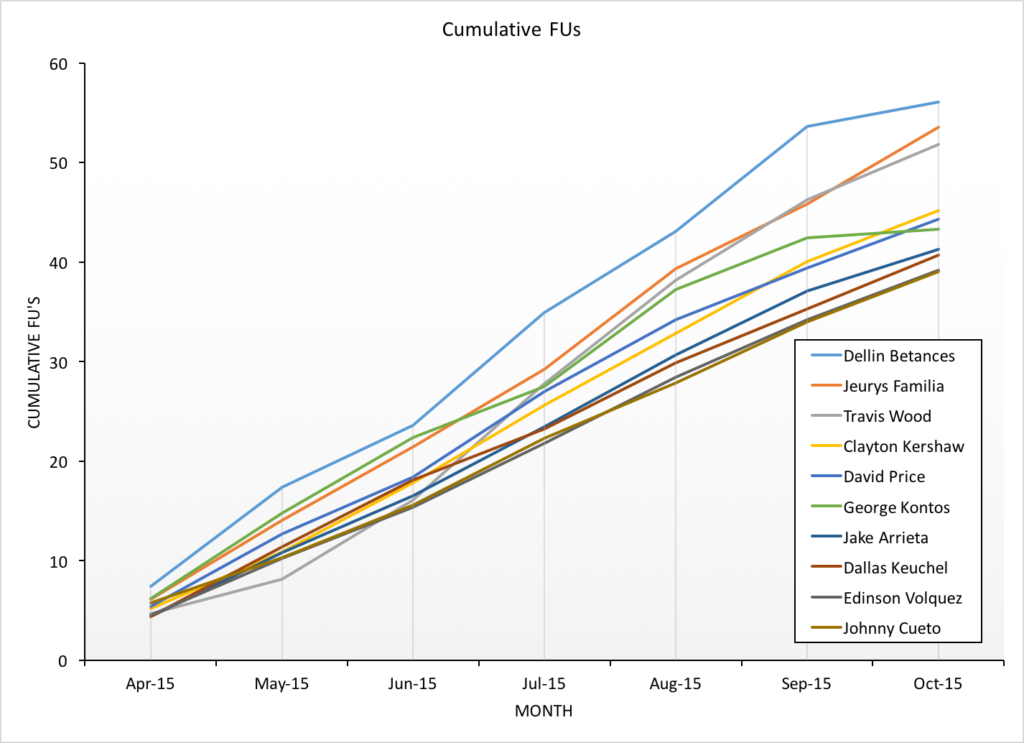

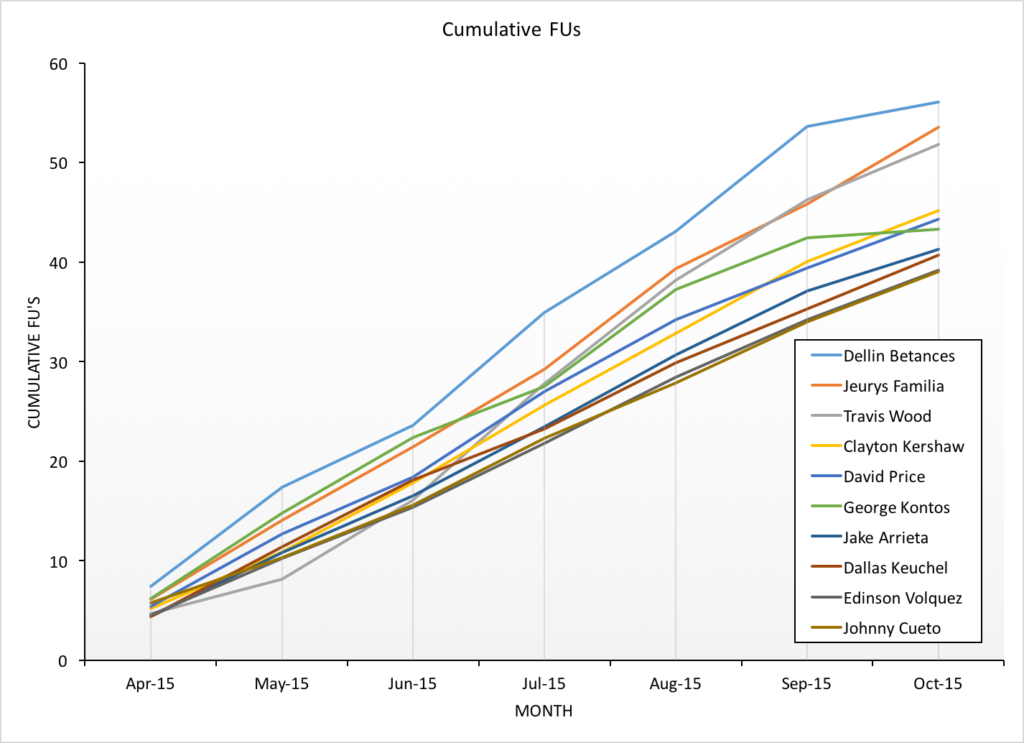

Figure 4. Cumulative FU’s for the 2015 season – top 10 pitcher workloads.

Once again, I don’t think it would surprise anyone to see Clayton Kershaw at the top of the innings pitched workload metric, or Jake Arrieta as the pitcher with the most total pitches thrown. These are both work horses for their respective teams. However, in both innings pitched, and total pitches, you will noticed that there are no relief pitchers.

Looking at cumulative FUs (Figure 4), Dellin Betances – he of 76 total game appearances, and Jeurys Familia (appearing in over 80 games for the Mets) appear at the top of the list. This is followed by Travis Wood (who appeared as both a reliever and a starter for the cubs), and finally, by Clayton Kershaw. Starters Price, Arrieta, Keuchel, Volquez and Cueto round out the list. This workload metric appears to show more favour for relievers, who appear on short rest schedules, often throw harder, appear in more games than starting pitchers.

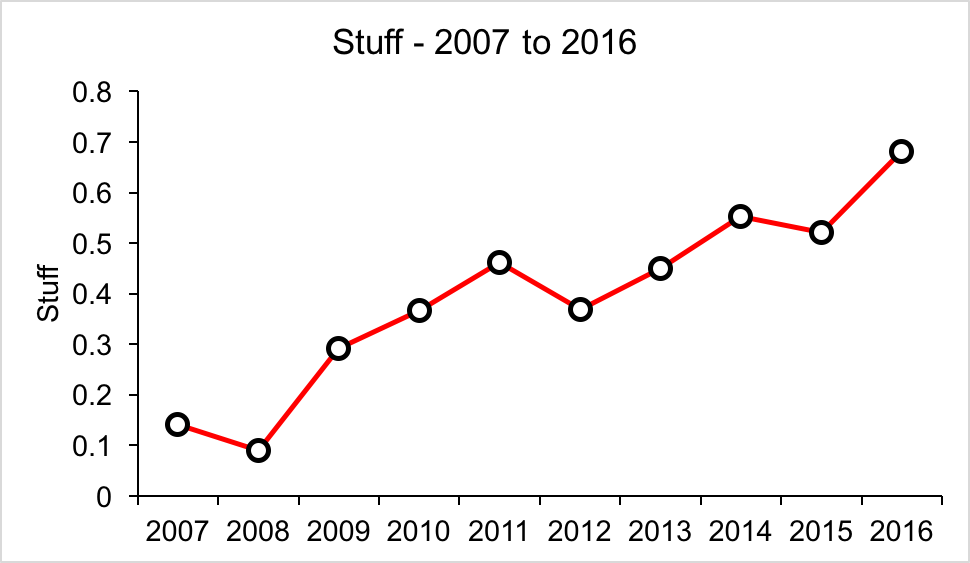

Let’s look one step further, and see who has the highest workloads between the 2007 and 2015 seasons. First of all – who cumulatively had the highest workload during this time, and second – who had the highest average workloads during this time period.

Table 1. Top 10 for cumulative FU’s between 2007 and 2015 (in blue). Top 10 for average cumulative FU’s in a season between 2007 and 2015 (in red).

Francisco Rodriguez has kind of run away with the cumulative FU crown – accumulating 366.19 FUs over the past 9 seasons. Serving as a closer – and surely, an elite closer, K-Rod has consistently averaged less than 3 days between appearances (on average, 2.7 days between appearances). Jonny Venters has the highest average season FU, at 49.64. His average days between appearances during those years with the Braves was 2.37. This is concerning, given his flame out of the major leagues due to injuries.

Depending on how you think about workload, these lists may surprise you. The overall cumulative workloads have half relievers, and half starters. The highest yearly averages all belong to relief pitchers, without a single starter in this list.

Even more concerning about the top seasonal workloads is the injury history of these pitchers – Venters and Manness needed Tommy John surgery after huge workload seasons, Trevor Rosenthal is down with a shoulder injury currently, and Belisaro flamed out of major league action. Carlos Marmol eventually lost all of his ability to throw strikes and is no longer on a major league roster. Even Francisco Rodriguez – who has remained relatively injury free (aside from a back injury) – is now throwing his fastball 5mph slower than he did in 2007. This is a legitimate concern for the number 3 pitcher on this list, the Blue Jays Roberto Osuna. As a teenager, Osuna had one Tommy John surgery – which is a risk factor for subsequent UCL reconstructions. Bear in mind – this list, and assessing workload with injuries, is completely anecdotal at this point. Much greater analysis is required to see if this workload metric is an indicator of injury potential.

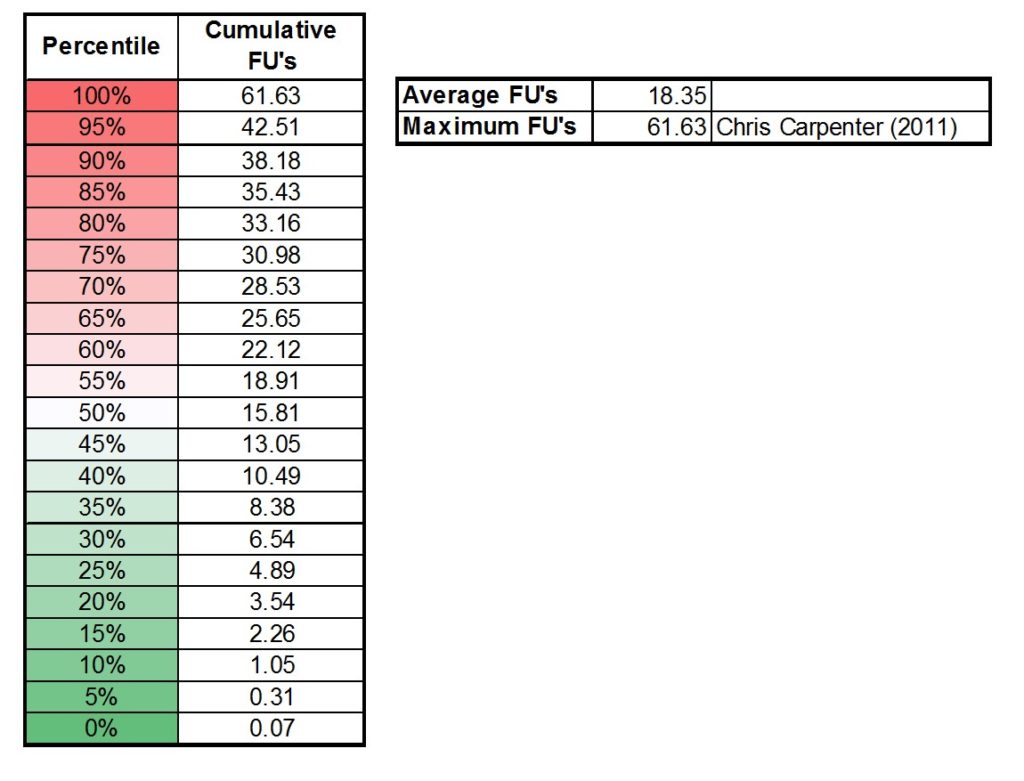

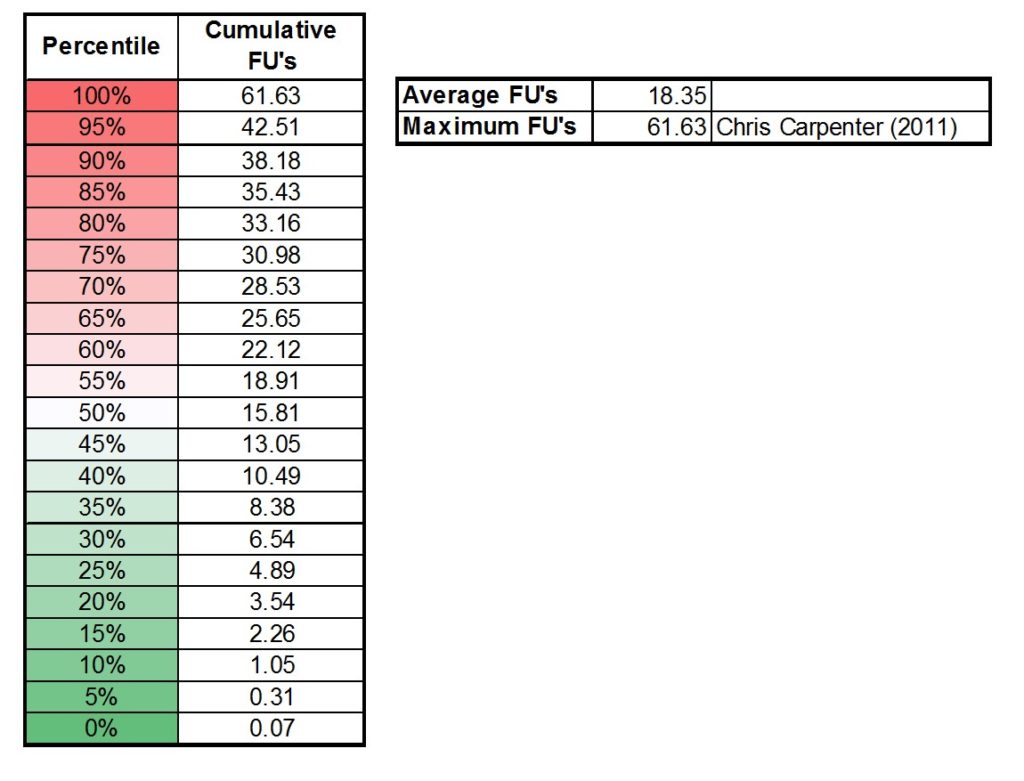

The next step – making this method easy to use, and finding out where threshold values lie. As for now, I can say based on these numbers – this is what different workload levels look like:

From a pool of 1869 pitchers, over the span of 9 seasons, this is the range we are seeing for cumulative FU’s. The average FU in a season is 18.35, and the maximum is 61.63 – from the 2011 season, which proved to be Chris Carpenter’s final season as a full time, major league pitcher. If someone gets to a level of 40, you can consider that a very high workload season.

Like all metrics, there is a long way to go for us to understand what exactly all of these numbers mean.

If you have any feedback, or questions about this method – shoot me an email (michaelsonne@gmail.com), or send me a tweet @DrMikeSonne.

If you’re curious, here are the data for different workload metrics.

References

Karakolis, T., Bhan, S., & Crotin, R. L. (2015). Injuries to young professional baseball pitchers cannot be prevented solely by restricting number of innings pitched. J Sports Med Phys Fitness.

Jazayeril, R. (1998). Pitcher Abuse Points – A New Way to Measure Pitcher Abuse. Baseball Prospectus, published June 19, 1998. http://www.baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=148

Whiteside, D., Martini, D. N., Lepley, A. S., Zernicke, R. F., & Goulet, G. C. (2016). Predictors of Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers. The American journal of sports medicine, 0363546516643812.

Sonne, M. (2016). Pitching Velocity and its Effect on UCLE stress using the Motus Sleeve. Driveline Baseball Blog, posted July 27, 2016.

https://www.drivelinebaseball.com/2016/07/27/pitching-velocity-and-its-effect-on-ucl-stress-using-the-motus-sleeve/

O’Connell, M., Boddy, K. (2016). Can You Reduce Pitching Elbow Stress Using a Sleeve? Driveline Baseball Blog, posted July 20, 2016. https://www.drivelinebaseball.com/2016/07/20/can-reduce-pitching-elbow-stress-using-sleeve/

Recent Comments